Introduction

The word “education” comes from the Latin verb “educare,” which means “to bring up” or “to nourish.”

The word “Shiksha” (Education) is derived from the Sanskrit root “Shiksh”, which means to learn and to teach.

Literally, education is the process that involves acquiring knowledge, studying, and developing skills.

Education is the soul of both an individual and a nation. It is not only a means of overall development, self-awakening, and consciousness but also the fundamental basis of social, economic, and cultural advancement.

Since ancient times, India has been renowned as the “Vishwa guru” (Teacher of the World). The history of the Indian education system is immensely glorious and rich.

In ancient times, the primary aim of education was self-realization, adherence to righteousness (Dharma), and the attainment of salvation (Moksha). However, in the modern era, the goal of education has expanded to include self-awareness, holistic development, and economic prosperity along with knowledge.

In ancient India, the medium of education was the Gurukul system, disciple tradition, oral recitation method (Parayan Vidhi), and Sanskrit language. In contrast, in the present time, education is imparted in schools, colleges, and universities in Hindi, English, and various regional languages with the help of modern technologies.

The development of education in India has passed through several significant stages—from the Vedic period to the modern era—making it one of the oldest and richest educational traditions in the world.

Education in the Vedic Age (1500 BCE – 600 BCE)

The earliest traces of organized education in India can be traced to the Vedic Age, which flourished approximately between 1500 BCE and 600 BCE. During this sacred era, the essence of learning transcended the mere acquisition of information. Education was conceived as a holistic process devoted to character formation, self-realization, adherence to righteous conduct (dharma), and ultimately, the attainment of liberation (moksha).

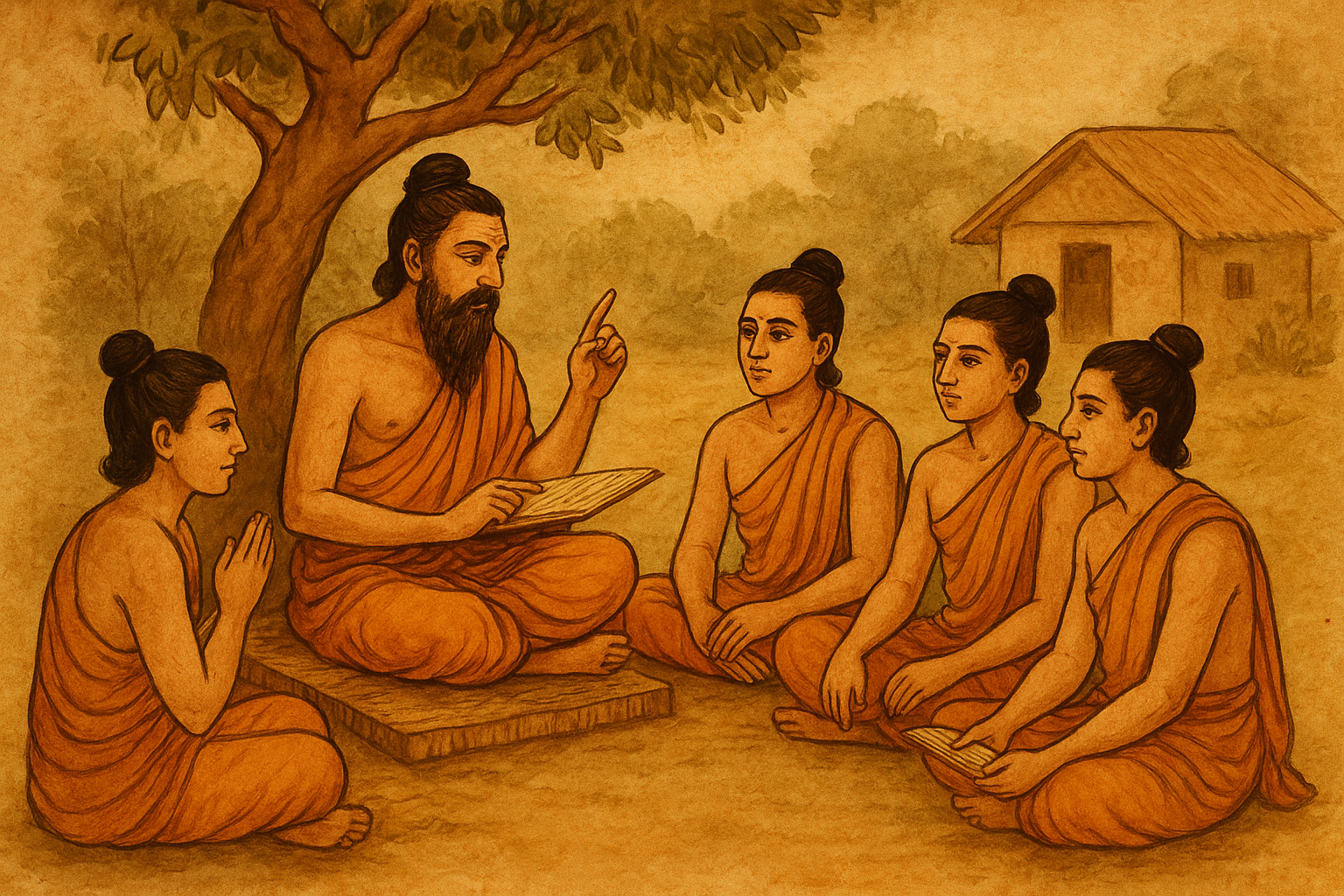

The Gurukul System: The Heart of Vedic Learning

Unlike the structured and institutionalized systems of modern education, Vedic learning lacked formal schools, examinations, and administrative frameworks. The Guru held complete authority as both the source of wisdom and the guardian of discipline. The entire educational framework revolved around the Gurukul system, wherein students (shishyas) resided with their Guru, receiving instruction through close personal association, observation, and disciplined living.

No fees were demanded for admission into a Gurukul. Instead, upon completing their education, students offered Guru Dakshina—a voluntary expression of gratitude and reverence—often in the form of cattle, service, or any offering desired by the Guru.

Method of Instruction and Language of Learning

Instruction was oral and conducted in Sanskrit, the sacred language of the Vedas. Knowledge was transmitted through the chanting and memorization of shlokas and mantras, which students mastered through repetition and imitation. This method, preserved through the twin traditions of Shruti (heard) and Smriti (remembered), relied profoundly on auditory learning, memory, and mental discipline. Assessment was not based on written tests but on the ethical conduct, behavior, and devotional attitude of the student.

Comprehensive and Holistic Curriculum

The curriculum of Vedic education was remarkably comprehensive, embracing both intellectual and spiritual dimensions. It included the study of the Vedas, grammar, ethics, philosophy, astronomy, mathematics, and martial sciences. Through this integrated approach, education sought to harmonize intellectual brilliance with moral virtue and spiritual insight.

Role of Women in Vedic Education

A distinguished feature of this age was the progressive role of women in education. Women were accorded the freedom to pursue learning and participated actively in intellectual and spiritual dialogues. Renowned female scholars such as Gargi Vachaknavi (after whom the Gargi Award is named), Maitreyi, Lopamudra, Ghosha, Aditi, Vishvambhara, Sulabha, Romasha, Sakta, Nivari, Indrani, Vishvara, and Devayani illuminated the intellectual horizon of their time through their erudition and philosophical insight. Their contributions exemplify the inclusive and enlightened nature of the Vedic education system.

Education as a Spiritual Journey

In essence, the Vedic system of education was not merely an academic endeavour—it was a spiritual journey. Knowledge was revered as sacred, teachers were honoured as divine representatives, and learning was regarded as the path to inner enlightenment and universal harmony.

Post-Vedic (Upanishadic) Education System

Post-Vedic education in India shifted focus from ritualistic purity to self-contemplation and philosophical reflection. Explore Takshashila, Nalanda, and Vikramshila universities.

The Post-Vedic period in India marked a revolutionary shift in education. Unlike the Vedic era, where learning was predominantly oral and focused on rituals, sacrifices, and ceremonies, Post-Vedic education emphasized inner self-contemplation, philosophical inquiry, and the pursuit of ultimate truth. This era witnessed the evolution of knowledge toward Brahma-Vidya (spiritual wisdom) and self-realization.

Several significant transitions occurred during this period. The move from oral to written education allowed for more systematic study, documentation of philosophical ideas, and the proliferation of learning centers. Under the patronage of enlightened rulers and visionary scholars, prominent universities emerged, shaping India’s intellectual landscape.

Great spiritual leaders like Gautama Buddha and Mahavira Jain played pivotal roles, not only initiating spiritual and social reforms but also contributing to education. Buddhist monasteries and Jain mathas became thriving centers of learning, blending spiritual teachings with intellectual growth.

The Shift from Vedic to Post-Vedic Education

Education in the Vedic age focused heavily on rituals, ceremonies, and memorization of the Vedas. The Post-Vedic period, spanning roughly from 800 BCE to 500 CE, redefined the objectives of learning. Knowledge was no longer merely about performing rites correctly; it was about understanding universal truths, ethical principles, and philosophical doctrines.

Students were encouraged to engage in critical thinking, self-reflection, and discussions. The Upanishads, composed during this period, became the cornerstone of philosophical education. This shift laid the foundation for a culture of inquiry and debate, influencing the development of logic, metaphysics, and ethics in India.

Emergence of Written Education

One of the most significant changes during the Post-Vedic period was the move from oral to written learning. Teachers and students began to document knowledge on palm leaves, birch bark, and early manuscripts, ensuring the preservation of texts and facilitating broader dissemination.

This written form enabled:

Standardization of teachings

Compilation of comprehensive treatises on subjects like medicine, astronomy, politics, and philosophy

Cross-regional exchange of knowledge

The ability to record and transmit knowledge systematically helped India become a hub of learning for students from Central Asia, China, Korea, and beyond

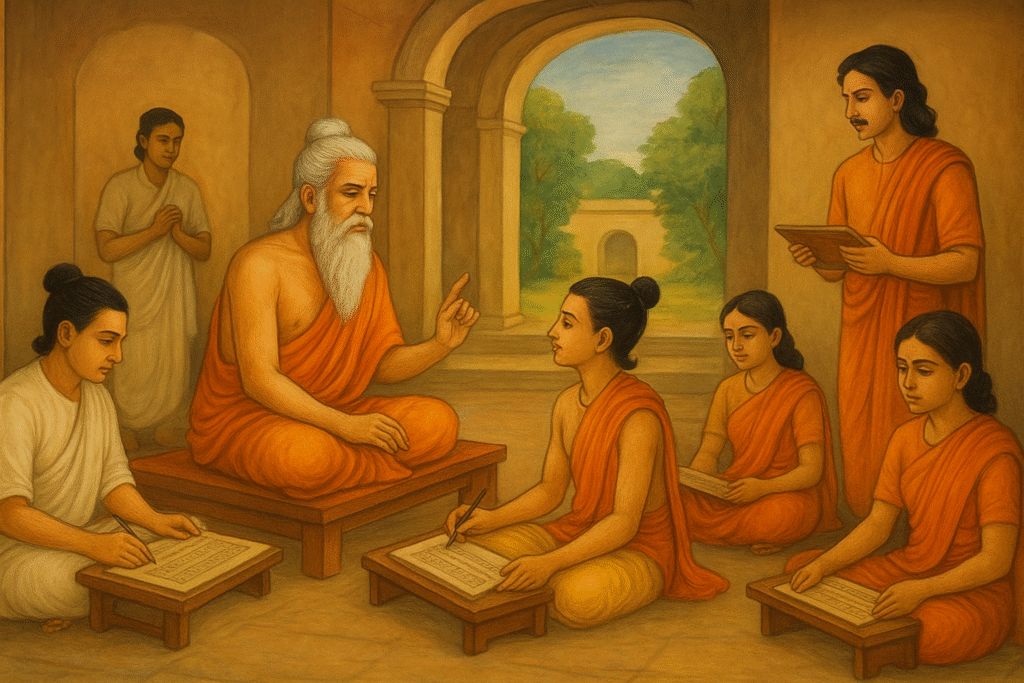

Patronage of Education and Learning Centers

Rulers and scholars understood the value of organized education. Under their guidance, great universities and centers of learning were established:

Takshashila (700 BCE) – Modern Rawalpindi, Pakistan

Nalanda (5th century CE) – Bihar, India

Vikramshila (8th century CE) – Bihar, India

Ujjain – Known for astronomy and mathematics

Vallabhi – Renowned for Sanskrit studies

These institutions not only taught traditional subjects but also included medicine, politics, economics, philosophy, and martial sciences, creating well-rounded scholars.

Spiritual Leaders as Educators

Figures like Gautama Buddha and Mahavira Jain were instrumental in integrating spiritual guidance with education. Buddhist monasteries and Jain mathas became intellectual hubs. Subjects included:

Ethics and morality

Meditation and self-discipline

Philosophy and debate

Literature and languages

This approach nurtured scholars who were both spiritually enlightened and academically accomplished.

Takshashila University: The Ancient Hub of Learning

Founding and Historical Background

Established around 700 BCE near present-day Rawalpindi, Pakistan, Takshashila is considered the world’s first university. It functioned as a major educational hub until about 500 BCE, attracting students from across the Indian subcontinent and beyond.

Education System and Guru-Shishya Tradition

Takshashila followed the guru-shishya model, where teachers imparted knowledge directly to students in their homes. Subjects taught included:

Vedas and Vedangas

Sanskrit grammar

Politics and economics

Medicine and Ayurveda

The personal mentorship model encouraged individualized attention and mastery.

Eminent Scholars of Takshashila

Panini – Authority on Sanskrit grammar

Chanakya (Kautilya) – Expert in politics and economics

Charaka – Legendary Ayurveda scholar

Atreya and Koushalya – Medicine instructors

These scholars produced seminal works that influenced generations of thinkers.

Major Sites of Takshashila

Bhir Mound – Oldest residential structures

Sirkap – Grid-patterned city with temples and palaces

Sirsukh – Developed during the Kushan era

Dharmarajika Stupa – Contained relics of Lord Buddha

UNESCO has recognized Takshashila as a World Heritage Site, highlighting its cultural, educational, and architectural significance.

Nalanda University: A Global Center of Learning

Foundation and Location

Foundation and Location

Nalanda, founded in the 5th century CE by Gupta ruler Kumaragupta I, was situated near Rajgir, Bihar. It became an international destination for scholars.

Admission Process and Student Diversity

Admission was rigorous, involving competitive examinations. Students traveled from China, Korea, Japan, Sri Lanka, Tibet, and Central Asia. Pilgrims like Xuanzang and Yijing documented the university’s thriving academic environment.

Library and Manuscripts

The library, Dharmaganja, consisted of three main buildings:

Ratnasagar

Ratnaranj

Ratnodadhi

Thousands of manuscripts covering philosophy, medicine, literature, and science were preserved here.

Destruction and Modern Revival

In 1193 CE, Bakhtiyar Khilji destroyed Nalanda. The library fire reportedly burned for several months, eradicating invaluable texts. Today, Nalanda has been revived as a modern educational and research institution, continuing its legacy

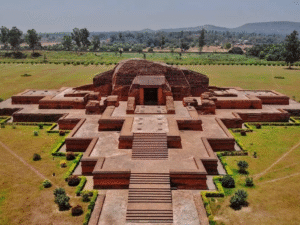

Vikramshila University: The Buddhist Academic Powerhouse

Founding and Historical Significance

Founded by Pala king Dharmapala in the 8th century CE, Vikramshila University was located in Antichak, Bihar. It became a major Buddhist learning center.

Founded by Pala king Dharmapala in the 8th century CE, Vikramshila University was located in Antichak, Bihar. It became a major Buddhist learning center.

Education and Curriculum

The university focused on:

Buddhist philosophy

Logic and debate

Literature and arts

Monastic education

It trained scholars who contributed to Buddhist missions abroad.

UNESCO Recognition and Present Status

In 2010, UNESCO recognized Vikramshila University as a World Heritage Site, acknowledging its historical importance. The ruins at Antichak remain a testament to India’s educational and architectural excellence.

University | Era | Location | Key Focus | Famous Scholars |

Takshashila | 700–500 BCE | Rawalpindi, Pakistan | Grammar, Politics, Medicine | Panini, Chanakya, Charaka |

Nalanda | 5th–12th CE | Bihar, India | Philosophy, Science, Literature | Xuanzang, Yijing |

Vikramshila | 8th–12th CE | Bihar, India | Buddhist Studies, Logic | Atisha |

These universities collectively shaped India’s intellectual landscape, creating a global reputation for advanced learning and scholarship.

Social and Religious Impact

Education as a Path to Liberation

Education was not merely intellectual; it was spiritual—a way to attain moksha (liberation from rebirth).

Caste and Accessibility in Education

Though spiritual equality was emphasized, caste barriers began restricting access to higher learning for lower social groups

Legacy of Post-Vedic Education

The Post-Vedic system left behind a legacy of philosophical thought, moral wisdom, and scientific curiosity, forming the backbone of Indian civilization.

Challenges and Decline

Over time, foreign invasions and social rigidity led to the decline of traditional learning centers and loss of ancient texts.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- What was the main aim of education in ancient India?

The primary aim of education in ancient India was self-realization, moral development, and spiritual growth, focusing on Dharma (righteousness) and Moksha (liberation). - What was the Gurukul system of education?

The Gurukul system was a residential form of learning where students lived with their teacher. It emphasized discipline, moral conduct, and holistic personal development. - How did the Post-Vedic education system differ from the Vedic one?

The Post-Vedic system shifted from oral and ritual-based learning to written education, philosophical inquiry, and establishment of major universities like Takshashila and Nalanda. - What were the major ancient universities of India?

The most renowned ancient universities were Takshashila, Nalanda, and Vikramshila, known globally for advanced studies in philosophy, science, medicine, and Buddhist learning. - Why did ancient Indian education decline?

Ancient education declined due to foreign invasions, destruction of universities like Nalanda, and increasing social rigidity that restricted learning based on caste and class.

Conclusion

From the sacred chants of the Vedas to the vast libraries of Nalanda and the profound discourses at Vikramshila, the journey of Shiksha in India reflects an unbroken quest for truth, wisdom, and self-realization. Rooted in the Sanskrit word “Shiksh”, meaning “to learn and to teach,” education in India has always transcended the mere transfer of information—it has been the awakening of the soul and the cultivation of virtue.

The ancient Gurukul system emphasized moral discipline and spiritual growth, while the great universities of the Post-Vedic era expanded the horizons of knowledge across philosophy, science, medicine, and art. Even as modern education adopts technology and new languages, the essence of Shiksha—the union of learning, ethics, and purpose—remains timeless.

India’s rich educational heritage continues to inspire the world, reminding us that true education does not just prepare us to earn a living, but to live with wisdom, compassion, and harmony. The flame of Shiksha, kindled thousands of years ago, still illuminates the path toward a more enlightened and humane society.

Read more at www.learnwithuss.com